Every educator has her own personal teaching philosophy. She demonstrates this teaching philosophy in ways such as choosing to use a group round-table discussion (instead of a lecture) or choosing to suspend the teaching of her content (even though it may make her a little behind in her lessons) so that the whole class can pray for Timmy because his favorite dog died last night and he is really upset. Sometimes she may take extra time to answer a student’s question, involving other students in the answer, so that everyone can learn that particular content. All of these situations are examples of choices made based on a teaching philosophy. In its simplest form, a teaching philosophy means the underlying reason the educator makes the teaching decisions she does (i.e., putting her beliefs into practice).

Know Your Class

Many of my teaching philosophy choices focus on what teaching strategies or what specific assignments (project or exam) I choose for my students. In teaching, I don’t choose randomly. I choose based on what I know about how my particular group of students learn. The more I know about the nature of students, the better choices I make for those students—and the better learners they become.

A basic “rule of the learner” involves making active learning choices specifically when the students (1) are younger or (2) are not native English speakers or (3) have weaker educational backgrounds or (4) need more time to process the information. These students need to be doing something in order to learn (NOT merely listening to something).

For example, I may have a group of students to whom I’m trying to teach good sentence writing. I already know that these students have not done well so far on their previous grammar assignments; so I determine they need more processing time and more involvement in the learning (i.e., active learning). Therefore, I would choose not to lecture about the seven types of sentences for most of my 50-minute class period. Instead I choose to demonstrate one type for a shorter period of time and then have the students practice using that one type. They will demonstrate their learning before I move on to the second type, and then the third type, etc.

Know Your Students

To extend my ministry even further, not only do I need to know about my learners as a group, but I need to know specifics about each of my learners. I may discover, for example, that one of my learners has a reading disability. This reading disability may affect his ability to choose the correct subject and verb in sentences only because he struggles to read the words (not because he doesn’t know how to make the correct choice). This type of student would profit from some adjustment in my teaching. If I (or his parents) read the sentences to him, he can make correct choices—because he is hearing them and not having to struggle to read them. (By the way, as a teacher, I have the legal [and ethical] right to research the records of each of my learners to determine if there is some specific information which would help me make even better teaching choices.)

Know What’s Most Important

I make good choices, as a teacher, when I know about my learners. And the more information I have about my learners, the better choices I make, which, of course, means the better learners they become. For me, personally, my most deliberate and important teaching philosophy choice is that each student with whom I work means more to God (and, therefore, to me) than the content I teach.

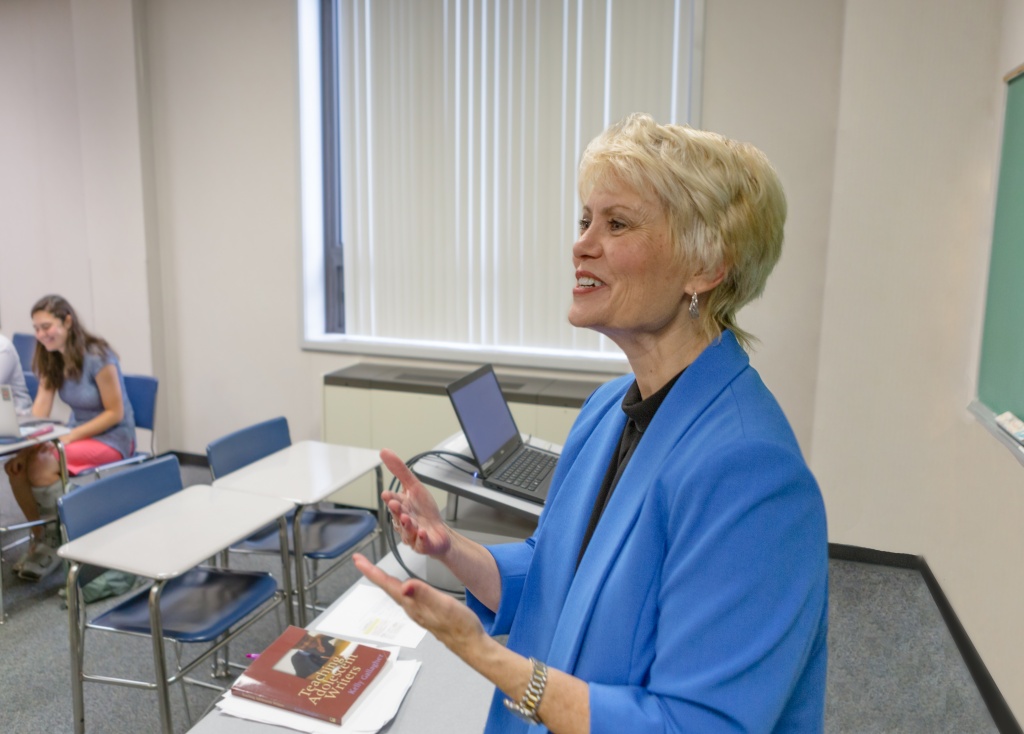

I have taught English to high school students and now teach educational methods to university students. (And yea for teaching!) No amount of educational content, however, is more important than any other need my student has. I am as concerned about the spiritual, physical and social well-being of each image bearer with whom I work (Luke 2:52) as I am with his educational well-being. So, it makes logical sense that the more I know about the spiritual, physical and social aspects of my students, the better choices I will make in meeting their needs.

For several years, I have taken seminary courses here at BJU. I began taking them as part of my doctoral work, and just last year I took another. In that one course, I obtained a better understanding of image bearers who are ethnically and culturally different from me. And I am excited about being able to fellowship and worship and learn with “every nation, tribe, people and language” (Revelation 7:9, ESV).

In my classroom, I have students who are different from me. And many have different problems than I do, and different plans, different goals, different dreams. It is a great joy to be able to minister to them and to fellowship with them spiritually. The more I learn, the better choices I make—and the better I can minister.

You and I matter to God. Students—people—matter to God. It is a blessing to know how to minister to those God places in our path.

This post was originally published on the CGO blog.